Water

| Gunts lay on the slope between two streams that flowed down to the Rigahn River in the deep ravine below. |

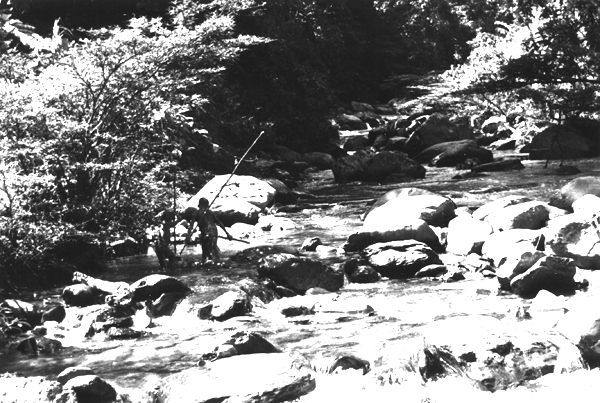

221-23: Where Golapai stream flows into the Rigahn River

| The Golapai was one of the two little streams that supplied our households, whose inhabitants varied in number from eight to twelve and more, including anthropologists, interpreters, work boys and passing visitors. |

| Our water requirements were entirely different from traditional Maring water usage. Our dishes, few as they were, needed to be washed - something the Maring did not have to do as they ate with their fingers and put their food on leaves which could simply be licked clean and thrown away. |

|

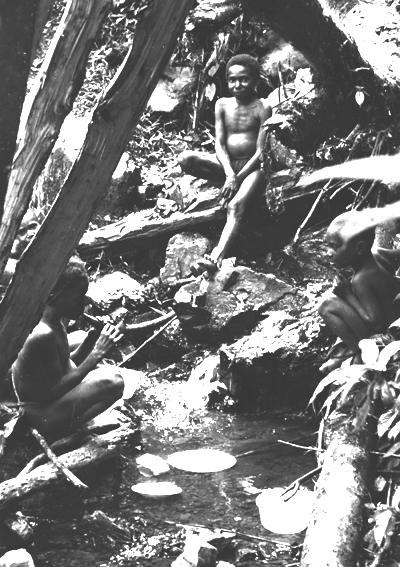

One day the younger work boys and their friends devised their own variation on the daily dishwashing chore: instead of bringing water to Gunts, they took the dishes to the water! | |

|

026-15: Washing dishes in the Golapai stream. |

| Water was required for more than

dish washing. Our diet was

based on water. We needed water for tea, for soups, and for the

rice that we brought in to lend variety to the local dependence on

sweet

potatoes and taro for basic carbohydrate. The Maring roasted

their tubers over a fire or steamed them in an earth oven together with

green leafy vegetables. |

| Rice had to be boiled, not only for ourselves, but also for the young interpreters who came from the Gai mission outpost and for our local “work boys” who wanted to be part of this enticing new world. They all lived together in the haus kuk and took part in preparing the necessary firewood. |  |

|

| 036-72: |

| There was also the matter of laundry. Traditional Maring clothing was not washed. Indeed, made out of local vegetable fibres, it was unwashable and was maintained by occasional wiping down with komba oil. The leaves that people covered their buttocks with were simply thrown away when they were wilted. But our clothing, and the much valued laplaps, T-shirts and shorts which, together with matches and trade tobacco, were also part of the normal wages of work boys, did require washing every few days. |

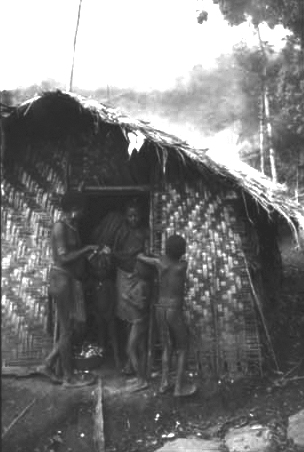

159-12: Mar and a visitor bring water to Gunts Yard.

159-13: All available containers are used, some already blackened

by the smoke from the open fire.

| And so buckets, teapots and dishpans entered the life-world of the Maring, together with bars of soap. |

| The daily custom of “wash-wash” for each “European” had already been established before Marek and I arrived. Each afternoon the work boys would heat water over the open fire in the haus kuk, pour the hot water into the shower bucket, and sling it from the heavy rafter in the shower room at the corner of our house. Then, wherever we were or whatever we were doing, Aikapo would decisively come to us with the announcement, “Wat’-wat’!” We felt guilty if we let all the work and firewood which had gone into the production go to waste, so we would drop what we were doing and obediently go take our showers. |

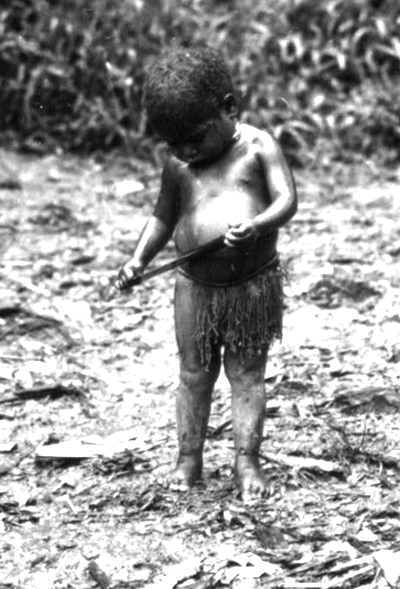

| Local people did not bathe as frequently as we did. They saved serious washing for just before ceremonial occasions. The American custom of giving children baths was unknown, and toddlers went around happily for days with dust all over their bellies, scraping it off occasionally if they got caught in the rain. |

192-01: Koram uses a big boy’s knife to clean her belly on a rainy afternoon in Tenegump.

| There were other fleeting and unique events that I was lucky to capture on film. When the Kiap was on patrol, taking the census of all the inhabitants of the lower Simbai Valley, he and his police constables and carriers stayed for several nights at the haus kiap in Tababe. A great deal of water was needed for his entourage. There were not enough buckets in our households, so many of the bamboo water tubes - nink mung - were called into use to deliver the needed water to Tababe. |

|

|

|

| 159-20, 159-22: A line of kids from Gunts carry water to Tababe in the nink mung belonging to several families. |

| Written in July, 2011 |

Copyright © 1999-2011 Allison Jablonko. All Rights Reserved.