Mbuk kongong

| Before the Columbia team arrived in the Simbai Valley, the local people already had some inkling about the importance of “the book.” The book that all of them were familiar with was the census record kept by the Patrol Officer - the kiap - in Simbai. Whenever he did the census rounds, this book was brought along and new entries - births, marriages and deaths - were duly entered. |

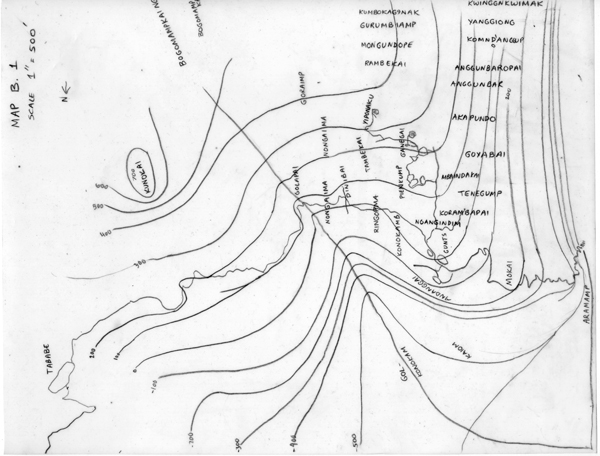

| When we got to Gunts, people saw daily the process of writing - in the little fieldnote books that we carried around to record on-going activities, and on sheets of paper to record our mapping efforts. |

An example of our mbuk kongong: A contourmap of Fungai territory

| Kids liked to sit by us as we watched people’s work and interactions. The children did not want to be left out of the action and would eagerly fill pages of our notebooks with careful markings. |

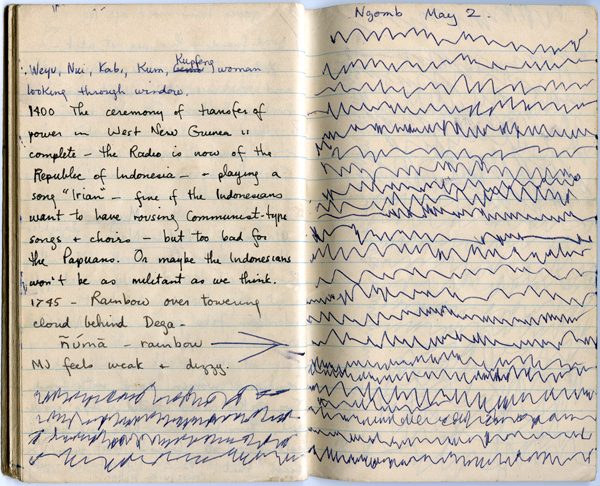

My field notebook # 3 open to the page of May 2, 1963

| Our efforts were referred to as mbuk kongong - work with a book. By using the term kongong, the activities of writing and drawing were equated with all the more obvious types of physical work necessary to Maring life. We were not just sitting around, but were pursuing our own kind of work. This, we had explained, was to write and make pictures that we could later share with people in our far-off home so they could learn about the skills the Maring brought to successful living. |

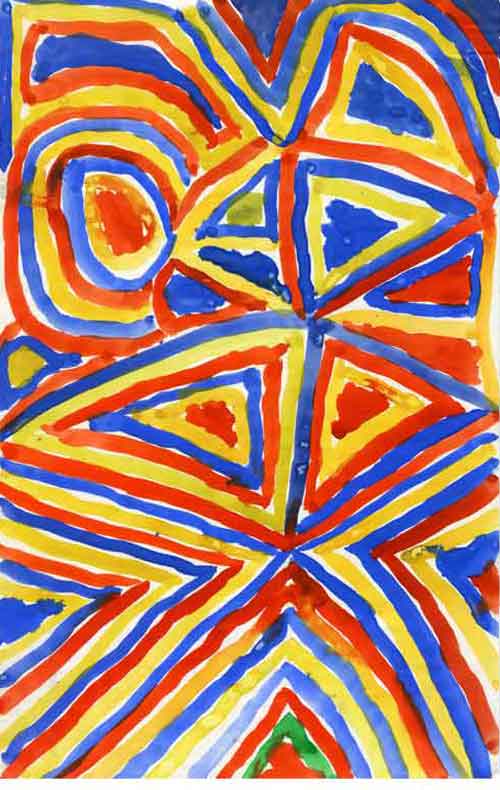

| Allison: “I no longer remember exactly how it was that the children started painting with the little watercolor set I had brought along thinking to spend 'spare time' sketching. I hardly ever got around to painting, but was happy to set people up with empty jars of water and show them how to keep the brushes clean. We handed out our typing paper and scratch paper, and tried to minimize what we considered 'scribbling' in our own notebooks. The field notes of June 7, 1963, indicate that it was a rainy day and Gomb and Kum, Minme’s daughters, together with Kunda and Tukume, were inside our house drawing. The next day, Gomb and Kum featured in the 'painting' photographs I took." |

038-12: On June 8, 1963 Wia and Gomb settle down to paint on the ground beside the Jablonkos' house.

| As it was a sunny day, people did not come into the house, but gathered at the northwest corner where Kum could reach through the window and paint on the surface at the end of the desk. |

038-13: Kum has set her water jar and paintbox on our desk just inside the window.

| We helped Gomb organize her paper on top of our bed roll at the other end of the house. The jar of water was placed safely on the pitpit surface of our bed/table. She could easily reach in through one of the windows. |

038-15: Gomb uses our bedroll as a surface to lay out her painting.

| When we saw the interest people took in

drawing and painting, we

bought additional sets of school paints and brushes from the trade

store in Madang, and handed them out whenever someone would come by and

ask to paint. Mostly it was the adolescents, but there were

occasional men and women who tried their hand. Over the course of

the year, we amassed a wonderful collection. These were some of

our favorite drawings. |

| The Rappaports had had a similar experience in Dikai. The walls of their living room were decorated with the results. After their departure, one of the young Tsembaga men who had worked for them, Akis, went on to study art in Port Moresby. Using the name Timothy Akis, he was one of the first internationally recognized artists from Papua New Guinea. Sadly, he died in 1984, before his career could fully flourish. |

| The full collection of drawings and

paintings made in Gunts during our

visit are archived together with the photographs and other materials. A small selection is available here: |

|

Completed on July 30, 2011

|

Copyright © 1999-2011 Allison Jablonko. All Rights Reserved.